21 Apr The Human Cost of Keeping B.C. Running

How Trade Workers Are Facing a Crisis of Pain, Stigma, and Substance Use.

Every day, we benefit from the man-made aspects of the world built around us — towering skyscrapers that hold our offices, the convenience of the SkyTrain, climate-controlled homes, smooth roads, and other essential utilities that keep our lives running. While enjoying these things, have you ever considered who makes all this possible? Behind the scenes, it’s the skilled men and women in trades that build, maintain, and power these infrastructures we rely on across British Columbia. Our daily routines depend on countless systems working seamlessly in the background, and these hardworking people are often the bridge to keeping things like our economy, energy, and transportation up and running. To say those who work in trades are important is an understatement. In fact, specialized or skilled trades workers are considered front-line workers in Canada. These specialized tradespeople may work in construction, transportation, manufacturing, industrial or natural resources, and agriculture. You can imagine that, like other front-line workers, such as paramedics or teachers, these essential roles come with difficulties that can weigh on you. Many trade workers struggle to cope with these difficulties, often carrying burdens of addiction, depression, injury, and family stresses silently. Substance misuse and overdose within trade communities, specifically with men, has become so common that many refer to the issue as “the other pandemic.” We will go in-depth about what trades workers around British Columbia are facing, why this group fits into the opioid crisis, how they can fall into addiction, and different solutions that have come forth to aid in this phenomenon.

Tough Work, Tougher Expectations

The trades industry consists of multiple fields that rely on skilled craftspeople, including construction workers, electricians, carpenters, plumbers, and mechanics. These industries often require a form of education such as trade school and are characterized by physical labour and mechanical skills. While rewarding in pay and other factors, this industry can come with genuine, sometimes life-altering, challenges. To overview these and understand trade culture alike, we must return to the beginning. Humans have been dabbling in trades since the dawn of time. Grass houses, mud huts, Indigenous tipis, and cabins made from wood and stone are all examples of early construction by humans for survival. Construction and trade as an industry in Canada formed around the nineteenth century, powered by steam engines, railroad development, and early machinery. The industry boomed during the 1990s, with total construction activity valued at $100 billion in 1902. When these industries were formed, they relied on hard work off the backs of men at their own expense. Offering countless hours, rough working conditions, no days off, and an expectation to persevere through injuries. In a time when the patriarchy was booming, the culture created in this workforce was a boys club founded on the belief that “true men” should be able to tolerate harsh working conditions. Much of what affects trade workers today stems from the scruff culture implemented many years ago. Below, we will go in-depth about some of the main difficulties of being in trades.

Stigma in the Workplace

The patriarchy demands men to be stoic and tough. Working on a construction site or a trades environment is one of the places where, in 2025, it can feel like you’ve been transported back in time. Inappropriate jokes in the name of bonding, “locker room talk” on-site, and an emotionally closed-off environment contribute to this. Thankfully, things are improving, but there is still an air of toxic masculinity over many worksites. We usually discuss how this may deter women in the field, the discrimination they face, and the difficulty of fitting in and feeling comfortable. Similarly, this type of environment also negatively impacts the men working in it. While there’s a sense of camaraderie, a “boys club” worksite may have pressure to act in a dominant way that ends up being harmful, encourages a dog-eat-dog work style, undermines the well-being of their workers, and also emphasizes self-reliance in cases where support is needed.

Long Hours and Overtime

Those in trades are often exposed to shift work, long hours of manual labour, and overtime. Shift workers, particularly, are at high risk of sleep deprivation as their routines don’t align with natural sleep-wake cycles and the body’s circadian rhythm. Oftentimes, shift workers switch between day, afternoon, and night shifts, making it even harder for their bodies to adjust to a schedule. Exhaustion from work leads to decreased efficiency and makes workers more likely to injure themselves on-site. Rules set by the Canadian government state that if you work more than 44 hours a week or 10 hours in a day, you must be paid an overtime rate. While it’s great that workers are compensated for their overtime, it does not change the exhaustion that comes from doing manual labour while working these hours. Workers will push through the hours, shift work, and physical strain silently, oftentimes leading to a precarious work-life balance and a general sense of tiredness even when not at work.

Physical Demands and Injuries

As mentioned, trade work is commonly associated with some physical labour aspect. Almost every job in this field involves lifting and bending movements. Other tasks, such as working at heights, operating heavy machinery, repetitive movements, and exposure to hazardous materials, significantly increase the likelihood of injury or fatal accidents. If you were to speak with someone who’s worked in the trades industry, they most likely have multiple stories of close calls or injuries from their time working. In 2022, approximately 348,747 accepted lost-time injury claims were filed, and 18,131 disabling injuries were reported. These statistics highlight the frequency with which workers face hazards on the job. Chronic pain is an epidemic in itself, stemming from the continuous manual labour workers face and, potentially, from the continued pain of an initial workplace injury. In Canada, as many as 75 percent of workers in the construction industry report experiencing ongoing musculoskeletal pain.

When Coping Becomes a Crisis

We all have ways of coping with our stressors, some healthier than others. Productive coping methods could include exercising, writing out your thoughts, watching a comfort show, or going for a walk. Working in trades, a culture where struggling is frowned upon and signs of weakness put you at the back of the pack, managing stressors from work can look a bit different. These people may be scared to disclose their feelings, fearing being criticized or considered weak. Reaching out for support can be stigmatizing in a male-dominated workplace, and individuals in the industry are left feeling helpless or alone. For years, trade workers experiencing mental anguish did not have access to proper resources or even know where to look; in response, they may use alcohol or substances as a way to relieve stress. Many workplaces have fostered a “work hard, play hard” attitude, expecting you to be more than happy to push your limits on the job. With the stigma around asking for help playing a significant role, pressure may be placed on the non-drinker to become one; this can be where the play-hard aspect comes in. According to the testimony of many construction workers, “real men” look forward to occasions when they can drink beer, and men who do not are considered to be effeminate. This sort of culture and thought process can reinforce and normalize unhealthy coping with alcohol and substance use. The statistics have shown this; an in-depth analysis of 872 overdose deaths from the B.C. Coroners Service showed that 55 percent of those employed at their time of death were employed in the trades industry. The vast majority of these deaths were men in their 30s and 40s, using substances alone. Research also shows that one in three construction workers across the country, union or non-union, reported “problematic substance abuse,” and one in two stated they felt that they had mental health issues they were struggling with.

Pain management, strain on the body, and injuries on the job are other ways that workers may fall into problematic substance use. Experts say a key factor in triggering many addictions is a WCB (workers’ compensation board) rule that injured workers must get back on the job promptly, often within days of getting hurt, even in some cases where their doctor strongly recommends against this. Several injured workers spoke up in an article from The Globe, mentioning that the only way they could cope with the demands to get back to work was to load up on painkillers, leaving them addicted and in far worse condition. A 2020 investigation found that doctors used by WCBs, which are designed to protect workers, were sometimes prescribing opioids after an injury, pushing people back to work, then cutting their benefits, eventually sending them towards an illicit supply. It can take only a week to become physically dependent on an opioid, so you can imagine how damaging this sequence could be. Some of these doctors see no issue with prescribing opioids and give little to no support or education on the possible dangers of these medications. Once someone is hooked and they are cut off from benefits, most cannot afford to pay out of pocket for prescriptions. This is where danger truly lies, as that person may now go to the streets towards the toxic drug supply. This exact cycle has resulted in an increasing number of illicit drug poisonings among trade workers.

A Lethal Evolution

Drugs offered on the street are far from what they once were. In 2025, the illicit drug supply is entirely a gamble. Fentanyl and other cheap, potent substances, such as Xylazine, have made their way into almost all street drugs. This happens because dealers can stretch their supply, maximize profits, and deliver a higher potency and longer high. Tampering with the supply this way has made street drugs increasingly dangerous, affordable, and powerful. Fentanyl, for example, can be mixed or “cut” with substances such as methamphetamines or cocaine, then pressed into pills to mimic common prescription opioids. In a study published by The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction in 2020, they found that nationally, fentanyl or similar substances were present in nearly two-thirds of opioid-containing samples. Among survey respondents with a fentanyl-positive urine screen, over one-third in B.C. did not report consuming this, suggesting they were unintentionally or unknowingly exposed. Nowadays, each time you use any drug that’s not from a controlled source, you are taking a gamble with your life.

Hardy Leighton from North Vancouver and his family understand this struggle all too well. Hardy’s family shared his story in an article by The Globe written in 2020. They shared that in 2010, Hardy critically injured his neck while working as a carpenter on a construction site. He then began taking opioid painkillers to cope with the pain. After Hardy’s accident, the provincial agency pushed him back into the workforce while he was still in pain, then later cut his benefits. In 2015, Hardy ended up overdosing on a mix of prescription and street drugs, including fentanyl. You could make a highly educated guess that his introduction to opioids, pressure to return back to work while still in pain, and the termination of his benefits for painkillers helped to sadly lead Hardy to this outcome. The provincial agency also failed to acknowledge his opioid addiction and didn’t respond to his pleas for help. Pain specialists and workers’ advocates blame this model from WCB as a reason for triggering countless addictions over many years and exacerbating the opioid crisis. Cecil Hershler, a Vancouver MD, has been a physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist for over 30 years. He is one of many doctors frustrated by how workers’ compensation systems push people back to work without giving them enough access to specialized diagnostics or non-opioid treatments. “I’ve got people from all walks of life, all ages, and they are crying. They will say, ‘Give me anything to take this pain away so I can get back to work, ‘” says Dr. Hershler.

Looking Ahead

Thankfully, the correlation between the mental and physical health of trade workers and substance use has been recognized for some time now. Specific programs and policies have been implemented in the last few years that offer a light at the end of the tunnel. There are now support and resource options for workers, and many advocates are determined to break the stigma around asking for help and toxic masculinity in the workforce. Providing naloxone on workplace sites is one way to reduce the stigma around drug use and make safety accessible. In British Columbia, workplaces have no official requirement to have naloxone kits available in 2025. However, employers can use the Joint Task Force Risk Assessment Tool to determine if naloxone should be available at their workplace. If eligible, individuals can receive naloxone kits at no cost, as well as overdose prevention and response training. On June 1st, 2023, it became law in Ontario that businesses that employ people at high risk of overdose, such as construction sites, must have a naloxone kit in the workplace and training on how to use it. We hope that other provinces will follow suit in this legislation, as it can reduce the rate of deadly overdoses in workplaces and show, from the employer’s side, a greater sense of care toward their employee’s safety.

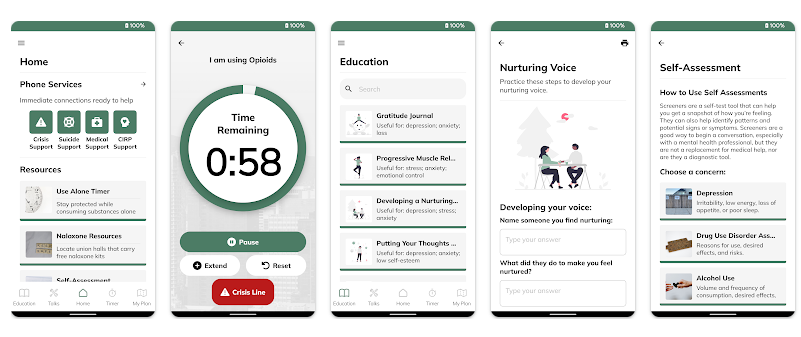

Programs like TailgateToolkit and the Construction Rehabilitation Plan (CIRP) have shined a light on the issues trade workers face and put forth a considerable effort to reduce the overrepresentation of men in illicit drug poisonings. CIRP, in particular, is a non-profit and joint union/management-sponsored alcohol and drug treatment program, providing mental health and substance use services within the trades industry in British Columbia and the Yukon Territories. They have 35 years of experience in this field, primarily focusing on managing stress & anxiety, physiology of mental health and addiction, suicidality training to staff, enhancing coping skills, and improving the quality of life within this workforce. The CIRP organization has launched an app in collaboration with Lifeguard Digital Health Inc. called “BuildStrong.” The idea behind this app was to take the revolutionary technology of LifeguardConnect™ and tailor it to best support the demographic of trades workers. The Connect™ app values privacy and autonomy, which is perfect for the needs of this community. As mentioned previously, stigma is a serious barrier to getting support. Unfortunately, we cannot take a hose and wash the stigma away in a quick sweep, as it has deep roots.

While we work towards eliminating this in the workforce, we can keep workers safe in the meantime. In the instance of someone looking for help that’s not part of a union, they could be open to scrutiny or allegations of not being able to properly fulfill the needs of their job due to possible mental health concerns being reported. Someone working for a union is more protected against this, but they may still value their privacy and not want to report their concerns to a supervisor immediately. LifeguardConnect™ can keep those who do not wish to report safe by directly putting relevant support and resources in their hands. Not every person needs the same help or course of action. That’s why the app also features an equitable assessment based on the individual’s needs. For example, the first question may be, “Are you experiencing anxiety or depression symptoms?” and depending on the answer you give, the following screen has multiple possibilities. The upcoming questions will continue to be tailored to your answers, giving you the best resources, advice, and help that could fit your situation. The use-alone timer is a classic feature of LifeguardConnect™ that’s also included in BuildStrong, putting autonomous safety directly in the hands of those who need it.

A Hard Truth We Can’t Ignore

Our society would not be able to function without trade workers. To say their jobs and skill sets are vital is an understatement. Like other front-line workers, these important, hardworking people seem undervalued based on the care provided for them in their roles. Teachers are underpaid, doctors are overworked, and those in trades have their own burdens to bear. They often operate in high-risk conditions, suffer injuries, and are pushed into a “work hard, play hard” attitude. Until now, this group has lacked options for support in coping with these challenges. This, along with other factors, has led workers to look towards unhealthy mechanisms such as substance use. Men in trades have been overrepresented in drug overdoses for years; since 2016, around 3 out of 4 opioid-related deaths were men, and 30 to 50% of those employed worked in trades at the time of their deaths. This shows a systemic issue within the trade community, as well as how the ripple effects of inadequate support systems and pain, both physical and emotional, are mishandled in a way that can cost lives. It’s time to start working on how we can lower these numbers.

The first step towards change is acknowledgement, so it’s a hopeful sign that in the last few years, the government and other advocates have recognized and taken steps towards alleviating these difficulties. One of those steps is the BuildStrong app from Lifeguard Digital Health Inc. in collaboration with CIRP. BuildStrong is a cutting-edge application designed explicitly for trade workers. Not only does the rollout of this app support de-stigmatizing men’s mental health, but with the backing of government, advocates, and trade companies, it shows the working demographic that solutions are being crafted and there are people who care about their well-being. We hope to continue seeing proposals, such as BuildStrong, being brought forward to help remedy these statistics within trade communities. As a community, we can aid in this “other pandemic” by uplifting the men in our lives and reminding them that it’s okay to struggle and ask for help and that their well-being is more important than anything else.

Written by Bryn Hardy, Lifeguard Digital Health